My Hand Trembles While I Write This. . .

Eyewitness Accounts of The Great Hunger

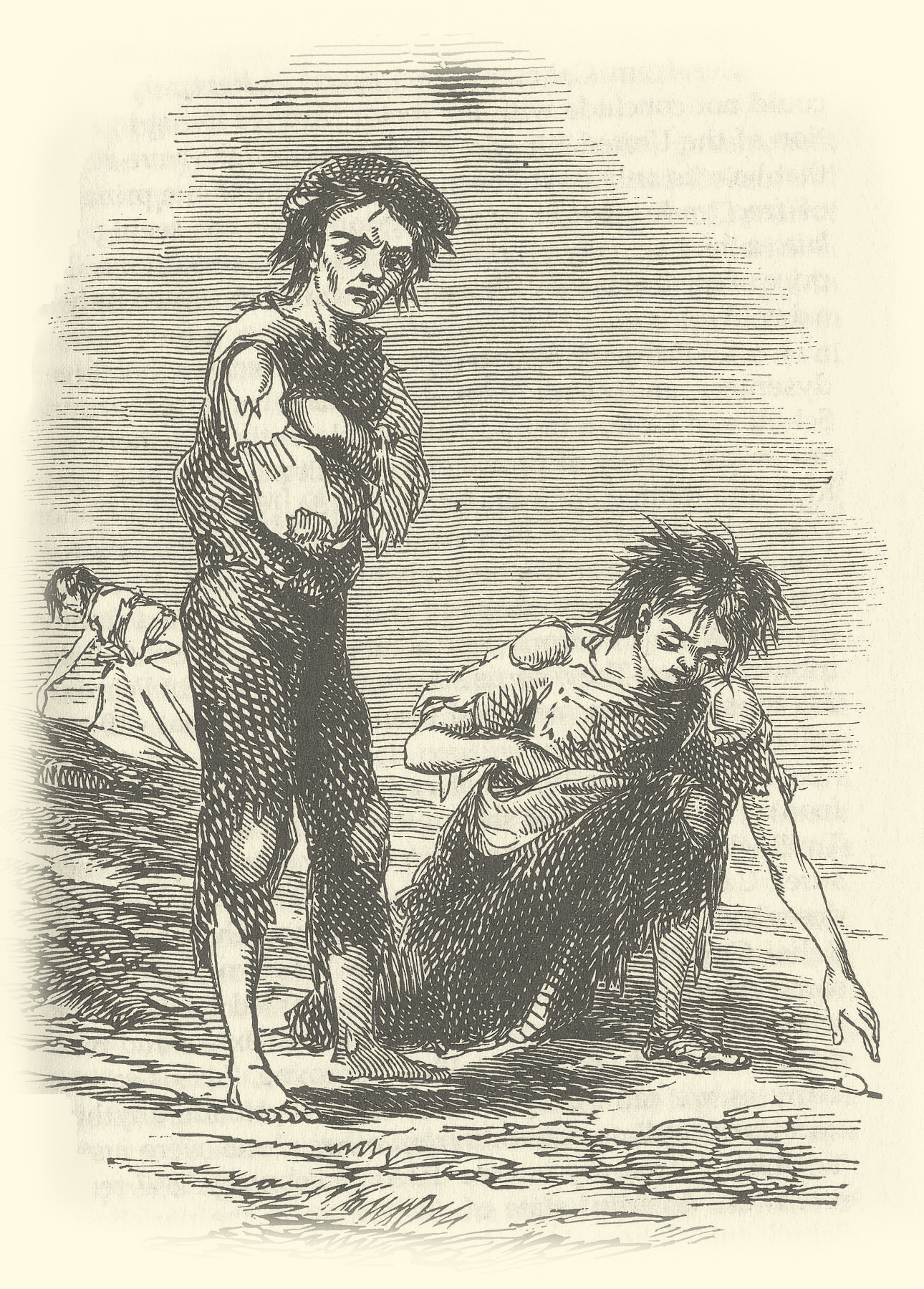

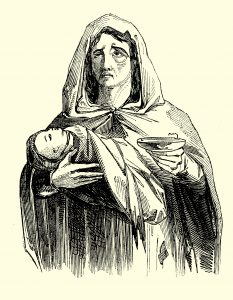

“I entered some of the hovels and the scenes which presented themselves were such as no tongue or pen can convey the slightest idea of. In the first, six famished and ghastly skeletons, to all appearances dead, were huddled in a corner on some filthy straw, their sole covering what seemed a ragged horse-cloth, their wretched legs hanging about, naked above the knees. I approached with horror, and found by a low moaning they were alive—they were in fever, four children, a woman and what had once been a man. It is impossible to go through the detail. Suffice it to say, that in a few minutes I was surrounded by at least 200 such phantoms, such frightful spectres as no words can describe, [suffering] either from famine or from fever. Their demoniac yells are still ringing in my ears, and their horrible images are fixed upon my brain.”

“I entered some of the hovels and the scenes which presented themselves were such as no tongue or pen can convey the slightest idea of. In the first, six famished and ghastly skeletons, to all appearances dead, were huddled in a corner on some filthy straw, their sole covering what seemed a ragged horse-cloth, their wretched legs hanging about, naked above the knees. I approached with horror, and found by a low moaning they were alive—they were in fever, four children, a woman and what had once been a man. It is impossible to go through the detail. Suffice it to say, that in a few minutes I was surrounded by at least 200 such phantoms, such frightful spectres as no words can describe, [suffering] either from famine or from fever. Their demoniac yells are still ringing in my ears, and their horrible images are fixed upon my brain.”

Nicholas Cummins, magistrate of Cork, visiting Skibbereen in 1847

“Will you believe me when I have to inform you that a poor woman from the Parish ofInniscarra, who through hunger, happened to pluck up a single turnip in the noon day, from one of the fields of Sir George Colthurst of Ardrum, was summoned to appear before theBench of Magistrates assembled at the Blarney Petty Sessions on Tuesday last, and fined for such trifling offence in the round sum of 20s. by the worthy magistrates.”

Letter to the editor, Cork Examiner, November 8, 1847

“. . .the people are in a starving state the poor house is crowded with people that are dying as fast as they can from 10 to 20 a day out of it there is some kind of strange fever in it and it is the opinion of the doctor it will spread over town and country when the weather grows warm no person can be sure of there lives one moment. . .”

“There is not room in the church yards for to bury the dead as they are dying so fast the coffins I may say are on the surface of the earth. . . .”

Letter from Hannah Curtis in Queen’s County Ireland to her brother John in Philadelphia 1847

“Catherine Sheehan, a child, two years old, who died on the 26th of December last, and had lived for several days previous to her death on sea weed, part of which was produced by Dr. McCarthy, who held a post-mortem examination on her body. The other details in this case are most heart-rending.”

The Times, Dublin, January 5, 1846

“Yesterday a man was discovered half concealed in a pigsty, in such a revolting condition that humanity would shrink at a description of the body. It was rapidly decomposing; but no neighbor has yet offered his services to cover the loathesome remains. Death has taken forcible possession of every cabin. Poor Coughlan, of the Board of Works, was crawling home a few nights ago, when hunger and exhaustion seized him within a few yards of his house, where was found the following morning, a frightening example of road mortality.

Cork Examiner report reprinted in The Times, January 18. 1847

“In a neighboring union a shipwrecked human body was cast on shore; a starving man extracted the heart and liver, and that was the maddening feast on which he regaled himself and his perishing family!”

Letter from the Protestant rector in Ballinrobe, reprinted in The Times May 23, 1849

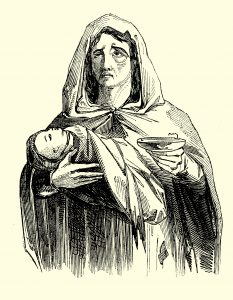

“A poor forlorn girl, hearing that her mother was seized with cholera, hastened to the rescue, alas! too late, but with a deep religious and filial devotion, desiring at least a decent interment for her dear departed parent, was driven to the shocking necessity of carrying the corpse upon her own back for three long miles to this very union, so that she might make her wants known, and simply obtain a coffin from the relieving officer. Need I tell you, my Lord, the dismal sequel? She herself died of cholera the next day. Those awful facts may have been reported, but if they were they have been cushioned and suppressed, for who has heard of them?”

“A poor forlorn girl, hearing that her mother was seized with cholera, hastened to the rescue, alas! too late, but with a deep religious and filial devotion, desiring at least a decent interment for her dear departed parent, was driven to the shocking necessity of carrying the corpse upon her own back for three long miles to this very union, so that she might make her wants known, and simply obtain a coffin from the relieving officer. Need I tell you, my Lord, the dismal sequel? She herself died of cholera the next day. Those awful facts may have been reported, but if they were they have been cushioned and suppressed, for who has heard of them?”

Letter from the Protestant rector in Ballinrobe, reprinted in The Times May 23, 1849

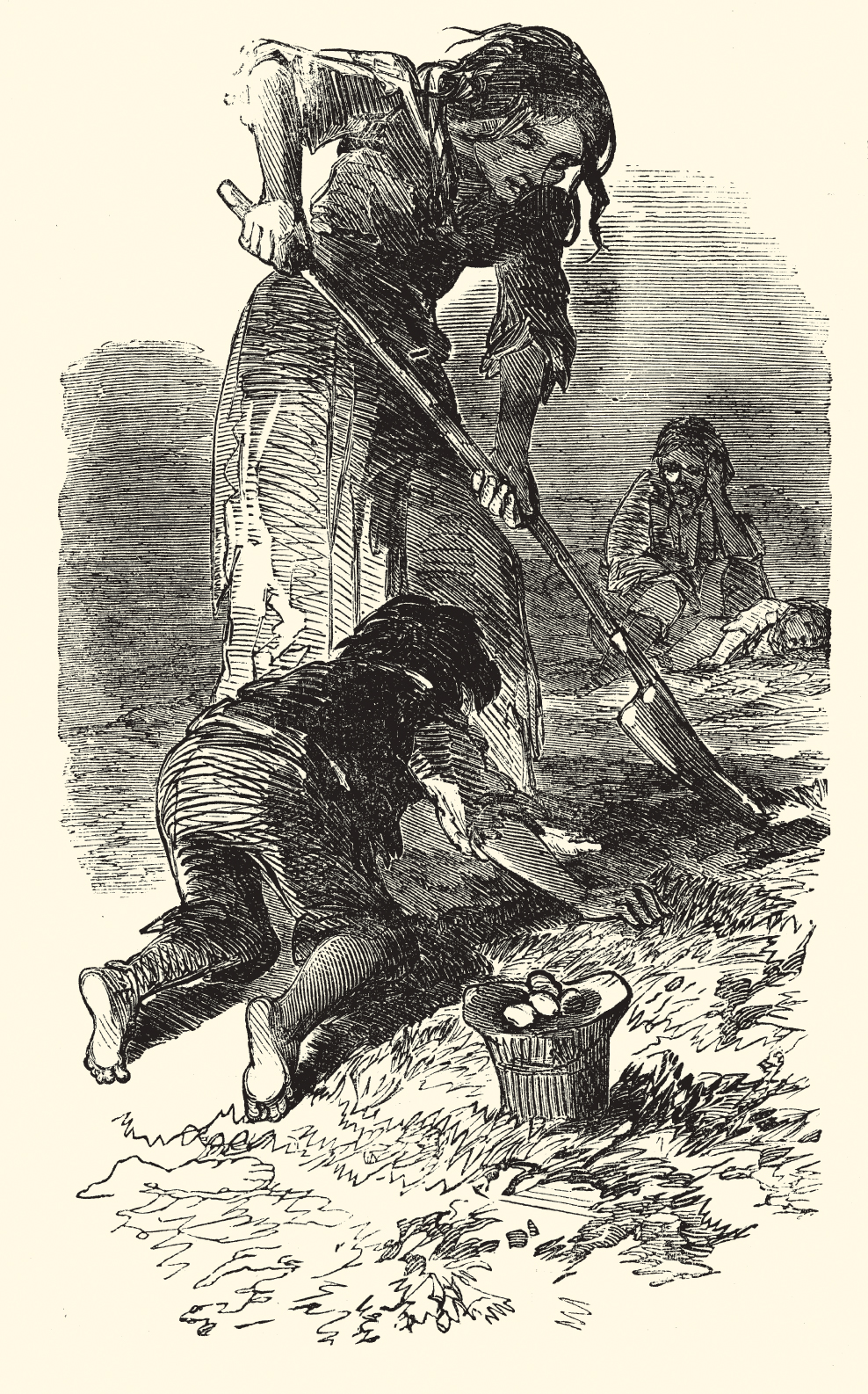

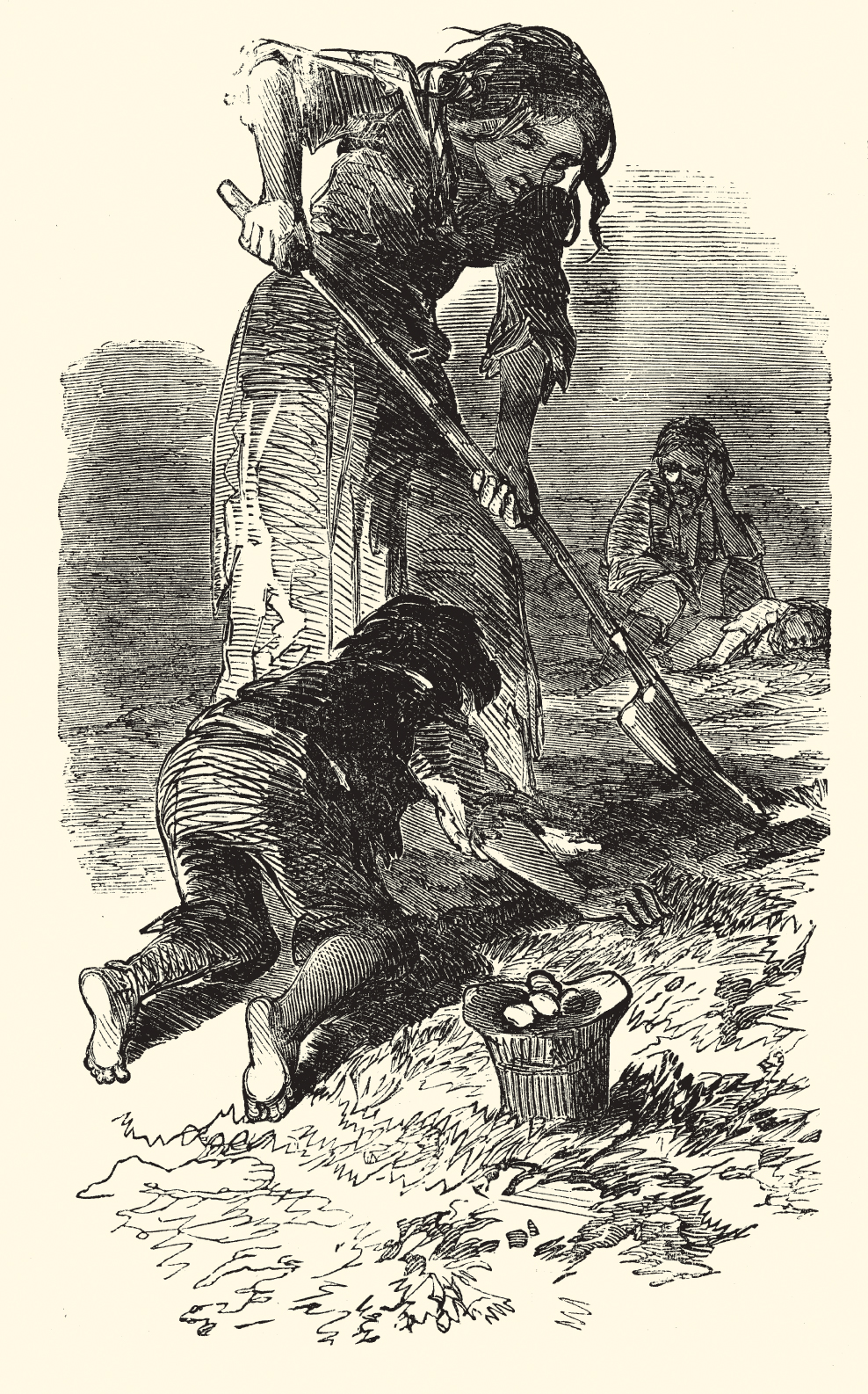

“On my most minute personal inspection of the state of the potato crop in this most fertile potato-growing locale, is founded my inexpressibly painful conviction, that one family in twenty of the people will not have a single potato left on Christmas Day next.. . . .With starvation at our doors, grimly staring us, vessels laden with our whole hopes of existence, our provisions, are hourly wafted from our every port. From one milling establishment I have last night seen no less than fifty dray-loads of meal moving on to Drogheda, thence to go to feed the foreigner, leaving starvation and death the soon and certain fate of the toil and sweat that raised this food.”

The Very Rev. Dr. McEvoy, October 24, 1847, writing from Kells, County Meath, Ireland

“We next reached Skibbereen. . .We first proceeded to Bridgetown. . .and there I saw the dying, the living, and the dead, lying indiscriminately upon the same floor, without anything between them and the cold earth, save a few miserable rags upon them. To point to any particular house as a proof of this would be a waste of time, as all were in the same state; and, not a single house out of 500 could boast of being free from death and fever, though several could be pointed out with the dead lying close to the living for the space of three or four, even six days, without any effort being made to remove the bodies to a last resting place.”

Artist James Mahoney, writing for the Illustrated Times of London,1847

“At a meeting of the Killarney Relief Committee, the Earl of Kenmare being in the chair, the parish priest, the Rev. B. O’Connor, made a statement, which, except as an illustration of the unprecedented misery to which the people had sunk, I would hesitate to reproduce. He said: “A man employed on the public works became sick. His wife had an infant at her breast. His son, who was fifteen years of age, was put in his place upon the works. The infant at the mother’s breast,” said the rev. gentleman, amid the sensation of the meeting, “had to be removed, in order that this boy might receive sustenance from his mother, to enable him to remain at work.”

James H. Tuke, a member of the Society of Friends, 1846

“This parish (Keantra, Dingle) contained, six months since, three thousand souls; over five hundred of these have perished, and three-fourths of them interred coffinless. They were carried to the churchyard, some on lids and ladders, more in baskets—aye, and scores of them thrown beside the nearest ditch, and there left to the mercy of the dogs, which have nothing else to feed on. On the 12th instant I went through the parish, to give a little assistance to some poor orphans and widows. I entered a hut, and there were the poor father and his three children dead beside him, and in such a state of decomposition that I had to get baskets, and have their remains carried in them.”

The Kerry Examiner, Feb 8, 1846

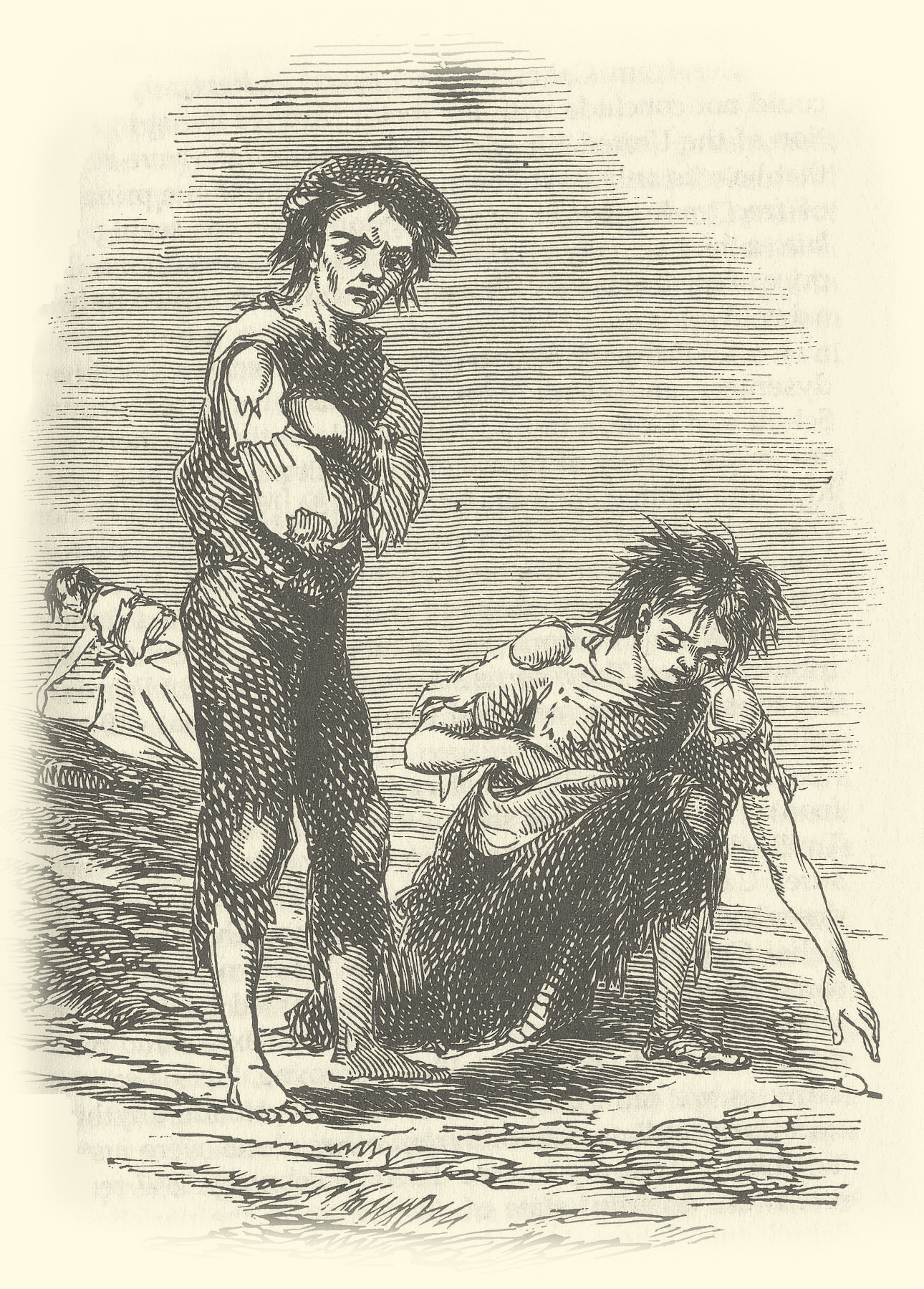

“The poor children” presented the most piteous and heart-rending spectacle. Many were too weak to stand, their little limbs attenuated, except where the frightful swellings had taken the place of previous emaciation, beyond the power of volition when moved. Every infantile expression entirely departed; and in some, reason and intelligence had evidently flown. Many were remnants of families, crowded together in one cabin; orphaned little relatives taken in by the equally destitute, and even strangers, for these poor people are kind to one another to the end. In one cabin was a sister, just dying, Iying by the side of her little brother, just dead. I have worse than this to relate, but it is useless to multiply details, and they are, in fact, unfit. They did but rarely complain. When inquired of, what was the matter, the answer was alike in all-‘Tha shein ukrosh,’ -indeed the hunger. We truly learned the terrible meaning of that sad word ‘ukrosh.”

“The poor children” presented the most piteous and heart-rending spectacle. Many were too weak to stand, their little limbs attenuated, except where the frightful swellings had taken the place of previous emaciation, beyond the power of volition when moved. Every infantile expression entirely departed; and in some, reason and intelligence had evidently flown. Many were remnants of families, crowded together in one cabin; orphaned little relatives taken in by the equally destitute, and even strangers, for these poor people are kind to one another to the end. In one cabin was a sister, just dying, Iying by the side of her little brother, just dead. I have worse than this to relate, but it is useless to multiply details, and they are, in fact, unfit. They did but rarely complain. When inquired of, what was the matter, the answer was alike in all-‘Tha shein ukrosh,’ -indeed the hunger. We truly learned the terrible meaning of that sad word ‘ukrosh.”

William Bennett, Narrative of a Recent Journey of Six Weeks in Ireland, 1847

“I entered some of the hovels and the scenes which presented themselves were such as no tongue or pen can convey the slightest idea of. In the first, six famished and ghastly skeletons, to all appearances dead, were huddled in a corner on some filthy straw, their sole covering what seemed a ragged horse-cloth, their wretched legs hanging about, naked above the knees. I approached with horror, and found by a low moaning they were alive—they were in fever, four children, a woman and what had once been a man. It is impossible to go through the detail. Suffice it to say, that in a few minutes I was surrounded by at least 200 such phantoms, such frightful spectres as no words can describe, [suffering] either from famine or from fever. Their demoniac yells are still ringing in my ears, and their horrible images are fixed upon my brain.”

“I entered some of the hovels and the scenes which presented themselves were such as no tongue or pen can convey the slightest idea of. In the first, six famished and ghastly skeletons, to all appearances dead, were huddled in a corner on some filthy straw, their sole covering what seemed a ragged horse-cloth, their wretched legs hanging about, naked above the knees. I approached with horror, and found by a low moaning they were alive—they were in fever, four children, a woman and what had once been a man. It is impossible to go through the detail. Suffice it to say, that in a few minutes I was surrounded by at least 200 such phantoms, such frightful spectres as no words can describe, [suffering] either from famine or from fever. Their demoniac yells are still ringing in my ears, and their horrible images are fixed upon my brain.”

“A poor forlorn girl, hearing that her mother was seized with cholera, hastened to the rescue, alas! too late, but with a deep religious and filial devotion, desiring at least a decent interment for her dear departed parent, was driven to the shocking necessity of carrying the corpse upon her own back for three long miles to this very union, so that she might make her wants known, and simply obtain a coffin from the relieving officer. Need I tell you, my Lord, the dismal sequel? She herself died of cholera the next day. Those awful facts may have been reported, but if they were they have been cushioned and suppressed, for who has heard of them?”

“A poor forlorn girl, hearing that her mother was seized with cholera, hastened to the rescue, alas! too late, but with a deep religious and filial devotion, desiring at least a decent interment for her dear departed parent, was driven to the shocking necessity of carrying the corpse upon her own back for three long miles to this very union, so that she might make her wants known, and simply obtain a coffin from the relieving officer. Need I tell you, my Lord, the dismal sequel? She herself died of cholera the next day. Those awful facts may have been reported, but if they were they have been cushioned and suppressed, for who has heard of them?” “The poor children” presented the most piteous and heart-rending spectacle. Many were too weak to stand, their little limbs attenuated, except where the frightful swellings had taken the place of previous emaciation, beyond the power of volition when moved. Every infantile expression entirely departed; and in some, reason and intelligence had evidently flown. Many were remnants of families, crowded together in one cabin; orphaned little relatives taken in by the equally destitute, and even strangers, for these poor people are kind to one another to the end. In one cabin was a sister, just dying, Iying by the side of her little brother, just dead. I have worse than this to relate, but it is useless to multiply details, and they are, in fact, unfit. They did but rarely complain. When inquired of, what was the matter, the answer was alike in all-‘Tha shein ukrosh,’ -indeed the hunger. We truly learned the terrible meaning of that sad word ‘ukrosh.”

“The poor children” presented the most piteous and heart-rending spectacle. Many were too weak to stand, their little limbs attenuated, except where the frightful swellings had taken the place of previous emaciation, beyond the power of volition when moved. Every infantile expression entirely departed; and in some, reason and intelligence had evidently flown. Many were remnants of families, crowded together in one cabin; orphaned little relatives taken in by the equally destitute, and even strangers, for these poor people are kind to one another to the end. In one cabin was a sister, just dying, Iying by the side of her little brother, just dead. I have worse than this to relate, but it is useless to multiply details, and they are, in fact, unfit. They did but rarely complain. When inquired of, what was the matter, the answer was alike in all-‘Tha shein ukrosh,’ -indeed the hunger. We truly learned the terrible meaning of that sad word ‘ukrosh.”