Journey to a New World

Passage and Emigration

In hopeless circumstances at home, the Irish fled their homeland by the hundreds of thousands each year. From 1845-1855, nearly a quarter of the population emigrated, mostly from rural, Catholic, often Irish-speaking areas of Ireland. They fled to England, to Australia, and in greatest numbers to North America, seeking new homes in Canada and the United States. Thus began a pattern of emigration that would become a psychic trauma in Irish life for over a hundred years. Read more…

In hopeless circumstances at home, the Irish fled their homeland by the hundreds of thousands each year. From 1845-1855, nearly a quarter of the population emigrated, mostly from rural, Catholic, often Irish-speaking areas of Ireland. They fled to England, to Australia, and in greatest numbers to North America, seeking new homes in Canada and the United States. Thus began a pattern of emigration that would become a psychic trauma in Irish life for over a hundred years. Read more…

Arrival and Reception

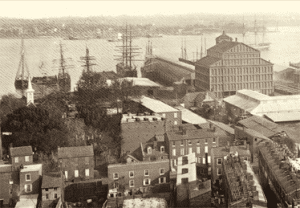

The New World was often hostile to this flood of impoverished Irish immigrants. In America’s cities, including Philadelphia, they arrived to face the native “Know-Nothing” movement, which defined “American” in terms that excluded the newly arriving Irish as “papists,” “foreign paupers,” “a motley multitude.” Most came from rural, agricultural backgrounds, but they landed in an urban, industrial world. Many had never been more than twenty miles from home before undertaking the hazardous transatlantic journey. Apprehensive, but eager to start a new life in freedom, they disembarked at ports like this one on the Delaware River in Philadelphia. However, when seeking employment, they were often greeted with the message “No Irish Need Apply.” Yet, by 1850, eighteen percent of the population of Philadelphia was Irish. Read more…

The Irish in America

The first wave of Hunger Emigrants faced enormous difficulties, but they found a foothold in what became America’s first urban, ethnic ghettos. Often, they lived in overcrowded hovels beset by disease, crime, unemployment, drink, and despair. Their communities were dubbed “Paddytown,” “Irishtown,” “Micktown.” But against great odds, they endured. They sought whatever work could be found, becoming newly industrial America’s cheap laboring force. They built railroads and bridges, dug canals and tunnels, went into mines, tended furnaces, worked as servants and seamstresses, and fought and died to preserve their new found home. Two hundred and sixty-three natives of Ireland would go on to earn the Congressional Medal of Honor, more than from any other foreign country. The Irish forged a cohesive communal voice by forming labor unions, political organizations, and cultural and religious societies. Gradually, they became Irish-Americans. Read more…

The first wave of Hunger Emigrants faced enormous difficulties, but they found a foothold in what became America’s first urban, ethnic ghettos. Often, they lived in overcrowded hovels beset by disease, crime, unemployment, drink, and despair. Their communities were dubbed “Paddytown,” “Irishtown,” “Micktown.” But against great odds, they endured. They sought whatever work could be found, becoming newly industrial America’s cheap laboring force. They built railroads and bridges, dug canals and tunnels, went into mines, tended furnaces, worked as servants and seamstresses, and fought and died to preserve their new found home. Two hundred and sixty-three natives of Ireland would go on to earn the Congressional Medal of Honor, more than from any other foreign country. The Irish forged a cohesive communal voice by forming labor unions, political organizations, and cultural and religious societies. Gradually, they became Irish-Americans. Read more…

The Lessons of the Great Hunger

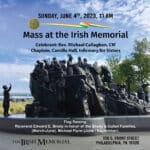

This memorial commemorates the struggle and pain of those Irish who fled their homeland in the face of a hunger of catastrophic proportions. It celebrates their courage and honors them for opening the door for others. Their story springs from one dark period in the history of a distant island, but their journey and arrival changed the face of American life and forged an enduring link between Ireland and America. Read more…

This memorial commemorates the struggle and pain of those Irish who fled their homeland in the face of a hunger of catastrophic proportions. It celebrates their courage and honors them for opening the door for others. Their story springs from one dark period in the history of a distant island, but their journey and arrival changed the face of American life and forged an enduring link between Ireland and America. Read more…